Amazulu, January 1984

"If there were more women in the music business we wouldn't be such a novelty."

I like this interview with Amazulu because it gives such a great picture of the socio-political context of the early 80s – the Greenham Common women, Thatcherism and feminism. I think this conversation was the first time I heard the notion that “the personal is political.”

At the time, we were in the middle of what’s sometimes called the “second wave of feminism”, something that had a huge effect on women of my generation. But there were still a lot of preconceptions about what feminism really meant, hence the reluctance of many female musicians to adopt the label.

From my memoir:

I asked all the women I interviewed the same questions: about how they chose to present themselves, how audiences responded to them, about feminism. I was interested in these things. Mostly, they weren’t. Like the Liverpool bands who didn’t want to be seen as “Liverpool bands”, most women in rock didn’t want to be “Women in Rock”.

I had more luck a few years later interviewing Amazulu, before they became pop stars, who were outspoken about politics and feminism. They told me, accurately: “The music business is dominated by men, like the world is dominated by men, and they want to keep it like that. They don't want women to be in on it, because women would find out how easy it is.”

This was more my sort of conversation. I was getting tired of hearing the word “groupie” from people who didn’t know that female rock journalists existed.

Then one of them had a question to ask me: “Do you have a spare Tampax?” I bet the men journalists never got asked that.

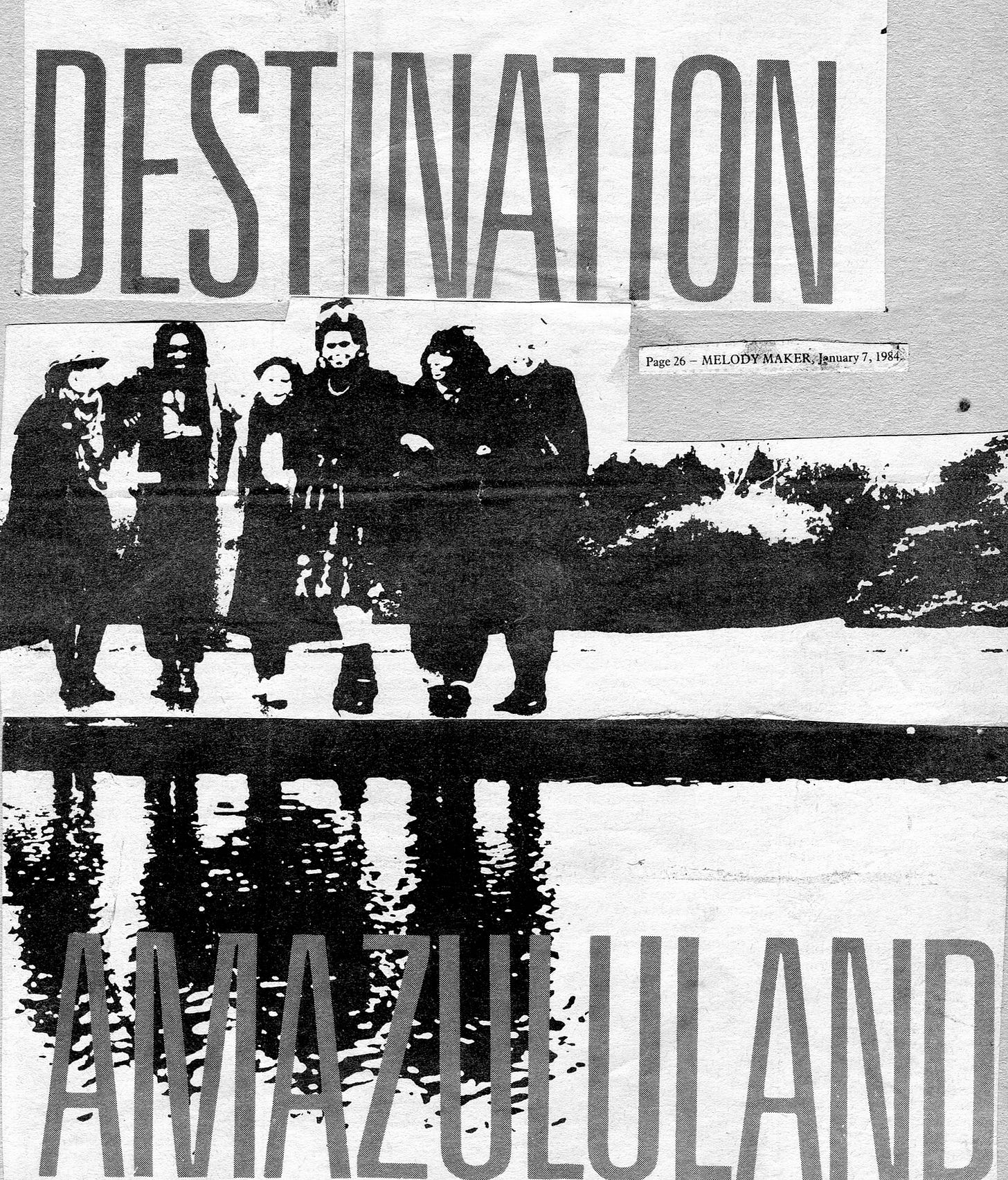

Destination Amazululand

Melody Maker, January 7, 1984

Penny Kiley digs up the truth behind almost-all-girl reggae band Amazulu.

THE most surprising thing about Amazulu is that people are still surprised by them. They should be charmed, delighted, inspired even, but not surprised. Not now.

But from the patronising praises that have patted the heads of these five females (conveniently forgetting the one man), you'd think that girls had never made music before. The "all-girl reggae group" - one-sixth male and playing something that goes beyond the confines of purist reggae - are all too readily viewed as something of a phenomenon, as if it's unusual to find a group of women showing the sort of strength that they have in abundance.

Amazulu are proof of what can be achieved, but they'd be the first to admit that they're by no means unique - and they'd hate to be seen as just an example ("We're just individuals expressing ourselves," says guitarist Margo).

Their powers of survival, though, are considerable. Anyone who can get through 12 (undeserved) days in a Finnish jail must have the sort of resilience necessary to meet any hurdles the music business can throw up. And hurdles there have been, almost from the start, not least because of the dangers involved when you grow up in public.

Most of the group were inexperienced when they joined Amazulu, and the glare of attention caused by the novelty of their line-up made learning difficult. The wrong kind of media attention, image manipulation, record company and management problems, and the vagaries of public and critical opinion, meant that the group, after almost two years of existence, are only now really finding their feet.

"We made some mistakes," admits Clare, the bassist, "but you don't really have that much choice to start with. Now we've got the guts to stand up and be ourselves, it's like a second chance now."

Now, with one record contract already part of the past, two singles to their name ("Cairo" and "Smilee Stylee"), a vast amount of touring behind them, and a by-now sizeable following, the group are looking to a future that this time will be in their control. The next step is a single on a major record label... on their terms this time.

"We've got confidence in ourselves now," says Lesley (saxophone). "With experience comes confidence, and we're not going to do what anyone says any more." It's time to move on: "We've been doing this for two years, and now we want to reach more people. It's time we started selling more records."

On a practical level, some sizeable record sales would mean less dependence on touring to pay the bills. Sharon (percussion) explains: "At the moment we don't have the money to tour on a comfortable level. We do enjoy the gigs but it's not that comfortable, the touring aspect of it."

When you consider that the group travelled 200,000 miles in 1983 you can understand their reluctance to continue this nomadic way of life indefinitely. I met the group in London, where they were headlining at The Venue, but they'd only just returned from a tour of Norway, and their descriptions of the trip made the threatening English winter seem almost mild. Travelling further and further north, the group found a corresponding drop in temperature, until eventually they had to admit defeat and cancel the final dates. "It was minus 45 degrees," Lesley tells me in awe. "I checked."

The group's experience in Finland last summer is still vivid in their minds, when they were imprisoned for 12 days following an alleged brawl with the crew of a ferry taking them from Sweden to Finland.

Lesley's anger returns as she recalls it: "We were stuck there without medical attention, without food, without warm clothing, without bedding. My poor dad read about it in the paper and nearly dropped dead. And the record company issued one statement: that we were all feminists. That made it sound like we started it, because that's the media view of feminism."

Sharon is certain that, after the initial receptiveness at the start of their career, that episode more than anything was what turned people against the group: "Nobody heard our side." They're understandably tired of talking about it now, but to put the record straight, the supposed fight was a purely unprovoked attack on the band.

"It wasn't as if we'd been boozing," says Clare. "We were just dancing. But they thought we were going to be trouble so they were watching all the time. Somebody took a swig out of a bottle of whisky in the bar - it wasn't even one of us, it was the promoter - and their reaction was totally over the top."

"They were dying for an excuse," adds Lesley, "just because we were different. That's all racism is - it was because we didn't look like them."

It must be difficult after that kind of experience to feel anything but bitter, but listen to Amazulu's music and it has a spirit that's not so easily broken. The records (even "Smilee Stylee", rushed out in the group's absence and felt to be unworthy of them) have a carefree vitality that's a joy to listen to, as do their radio sessions, but they all agree that the full potential of Amazulu is yet to be captured in the studio; something that will be rectified very soon if their plans for a New Year single are fulfilled.

Hear the group on stage, though, and there's a warmth that's almost tangible, whether in the delightful fun of "Moonlight Romance" - irresistible for the feet - or "Tonto" - with its bizarre mix of styles - or, on a more serious level, the exuberant solidarity of "Greenham Time", or the almost spiritual affirmation of "Only Love".

"The more horrible things happen to you, the more you want to stop it,'' declares Lesley. They're continually battling against intolerance, but they don't give up easily, and if it's deeds, not words, that ultimately do most to change attitudes, then Amazulu inspire by their own example.

It goes a lot further, though, than demonstrating that, yes, women can do things for themselves, or that, of course, races can work and create together. The line-up, after all, was not deliberate: "There's exactly three black and three white in the group," admits Sharon, "but it just happened that way."

It's a cliché to talk about universal love and brotherhood through music, but when you watch Amazulu bouncing and smiling through their set, six individuals with a common purpose, you're seeing the words of their songs personified, and the sheer good humour of the event is enough to melt away cynicism. It proves that popular music can deal with a kind of love that's nothing to do with boy meets girl, and if that sounds like hippy nonsense, well, seeing is believing, so see them!

That kind of unity stems from sharing, and one thing about Amazulu is that they obviously care about sharing their music fully with the audience.

"You're all there for the same thing," reasons Lesley. "I'd hate to be in one of those serious bands that ignore the audience, it would really embarrass me."

WITH six thinkers in the band, it's hardly surprising that some forceful opinions appear in their music, but they don't consider themselves a political band. ("We do have songs that are just for fun," Clare reminds me.) If anything, they agree, the songs are about "everyday politics".

It's just our views of things that happen everyday," explains Lesley, "things that affect us. People say 'politics have got nothing to do with me', but they have, it's everyone's everyday life; when my mum goes 'oh look at the price of milk’, that's political."

More and more you can hear people talk like this, and even in the superficial world of showbusiness there's an increasing awareness that has to be communicated.

"I think it's because things are getting worse," confirms Lesley. "Everyone's thinking like that, people are more affected now. Five years ago it was easier to forget what was going on, but you can't ignore it any more.

"We wouldn't be classed as a political band though," she adds, "like before we were talking in the car on the way here, we might be in the van one day and start talking about something, it might not necessarily be political, and a song would come out of it."

That's how "Greenham Time", the B-side of "Cairo" came about. Lesley: "All the newspapers were writing about it and going on and on about them being lesbians - it's got nothing to do with the fact that they don't want to die. Nobody ever writes about what Margaret Thatcher does in bed! It got us so mad that day that we had to write a song about it."

That kind of media misrepresentation is something they're well aware of through their own experience. The reporting of the Finland incident still rankles, but it's something that, however subtly, has always dogged them.

"If there were more women in the music business we wouldn't be such a novelty," sighs Lesley, "and we wouldn't always be compared with the only other well-known girl band around." (The group express a fervent desire that this time, at least, they not be named!) "I don't like it when people compare us to other people," complains Nardo and Clare adds vehemently: "Everyone's an individual - we're not trying to look or sound like anyone."

As far as music goes, Amazulu, though widely accessible, are subtly different from the usual reggae crossover group. With a starting point of reggae, they don't dilute it to pop taste but, perversely, add further flavourings to give a richer mix. The resulting rhythms can be anything from "rock, calypso, or Latin", Nardo tells me.

"Country and Western type vocals and harmonies," contributes Clare, "and we're even getting into funk now," she adds. "And we've got a jazzy song too."

Lesley tries to describe the ideal Amazulu sound: "The idea is to have a good heavy bass and drum reggae beat underneath, with different things on top." The result combines the danceability and humanity of the best reggae with the energy of the best rock, and the "sparkle and bite" (Clare's words) of the best pop.

Though using several conventions from reggae, when it suits them, and always employing a hard authentic beat, they won't be limited to "just sticking to what a lot of reggae bands stick to", as Lesley puts it. "We like the freedom to explore and experiment," says Clare. "We don't have closed minds about it."

Closed minds: that's what Amazulu always stand against, whether you're talking about music or in wider terms. Lesley is explaining why, in spite of their assertively feminine ideals, the group avoid the label feminists, with its stereotyped connotations: "Our main policy is non-separatism. There are so many little sections you're supposed to be in, and we don't want to be in any of them." Amazulu have spent most of their career so far trying to escape them.

Women in rock? "A lot of women think women can't get up on stage and play guitar and drums, that's it's a man's thing to do," says Sharon.

More militantly, Lesley explains why. "The music business is dominated by men, like the world is dominated by men, and they want to keep it like that. They don't want women to be in on it, because women would find out how easy it is."

Women in reggae?

"When we started, there might have been women in rock musicians by then," recalls Lesley, "but there were no women on the reggae scene. We were fed up to the teeth of going to see a reggae band and there were all the guys giving it loads, shaking their dreadlocks, and two girls, in a corner with scarves on, going 'bap bap' every five minutes."

See Amazulu singer Annie attack on stage - dreadlocks flying - and you'll wonder that girls could ever be considered passive.

And then there was racism, on both sides. "Another bridge we had to cross: 'white people can't play reggae'. And there are shocking examples of white racism in Amazulu's experience too.

"Racism is when people dislike other people because they're different from them," defines Lesley. "You don't even have to be a different colour, just wear different shoes..."

IN Amazulu everyone is different, and that's probably their secret. The audience - "hippies, rastas, student types, gay lib . . ." enumerates Lesley - reflect the mixture in the band: "Even apart from the different races, we've got different types of people, and because we're all different we might appeal to someone different."

"Everyone's from a different culture, a different style," says Nardo, "and it's unified because it's mixed."

Their performance that night confirmed it. It's not often you get something that's so entertaining and so positive at the same time. As the audience, together, danced, we heard the words of "Niya Deya", shouting "no more barriers - no more boundaries."

At the moment you could almost believe it possible. With a band like Amazulu, nothing should surprise.

Watch Amazulu

Here are Amazulu doing one of the songs mentioned in the article. Note the Cairo/Giro rhyme. Note for younger or non-UK readers: a Giro was a dole cheque (unemployment benefit).

"The music business is dominated by men, like the world is dominated by men, and they want to keep it like that. They don't want women to be in on it, because women would find out how easy it is.” Not unlike the rest of show business. They don't know what they're missing...

I had totally forgotten about Amazulu. What a great piece. They really did represent that time so well and on listening to them today, they sound great. Sadly, I feel they would still be a novelty.